A member of a web community I participate in posted the following:

Belief stems from fear of not knowing. In lack of sufficient knowledge, beliefs are imposed by the Ego in order to escape the insecurity of not knowing. This results in self limiting, as the beliefs prevent other possibilities from being explored by the mind. Beliefs are soothing to the Ego, and creates a dysfunctional mentality. Instead of accepting that you don't know, beliefs are created to fool you into thinking you DO know. Belief and fear walk hand in hand, being interdependent of each other. Destroy one, destroy the other. To achieve perfect enlightenment, eradicate fear through dispelling of beliefs. It takes guts to realize you basically know nothing.

I wanted to cross post my response to From Ashes:

I feel that some of this is true, or perhaps, I believe some of this to be true, but some of this I don’t believe.

I don’t believe, for instance, that all beliefs stem from a fear of not knowing. I think it is possible, and likely, that some beliefs stem from this sort of fear, but I feel that most of our beliefs do not. Indeed, it seems to me that much of our beliefs arise out of what it is we think we know. For instance, the fact that I believe, as likely do many of you, that ‘2 + 2 = 4’ is true has little to do with fear, but much more of our understanding and acceptance of a system of rules, of a way of speaking about things. Further, beliefs that we hold about facts of the matter also seem to have little to do with fear, and more extend from what we feel we know about these same facts of a given matter. That I believe that there is beer in the fridge, for instance, has to do with several interconnected observations, a primary one includes the observation that the last time I got a beer from the fridge there was still more beer in the fridge, coupled with the knowledge that I had placed several beers in the fridge in the first place! It seems to me that much of the beliefs we use to navigate our lives are based on what we have observed: these observations form the knowledge base from which we create many of our beliefs about the world.

Given this partial disagreement, however, I am compelled to agree that all beliefs—whether formulated from that which we feel we know or from that need “…to escape the insecurity of not knowing”—are indeed limiting factors which “…prevent other possibilities from being explored by the mind.” It doesn’t matter how we have come to form our beliefs—through knowledge or through ignorance—all beliefs serve to define what we feel to be reality, and in this determination some set of possibilities are taken to be actualities at the expense of some other (likely larger) set of possibilities which necessarily go unexamined and unexplored, and thus, undifferentiated and unactualized.

Also, it seems to me that, yes, enlightenment (whatever that may actually be) requires a dispelling of fear—I don’t see how we would experience an enlightened state of being that was also a fearful state of being; although, perhaps there is something to be said for experiencing some state of fear in relation to enlightenment (here with respect to the notion of mysterium tremendum et fascinans). Further, I tend to agree that experiencing enlightenment also requires that we abandon beliefs. With regards to the notion of the nominous mentioned in the previous link, I feel that there is an interdependence between experience of the “wholly other” and the experience of enlightenment. Perhaps this interdependence might be regarded as the absorption of ego into the wholly other and the identification of the Other with the Self, which together preclude some sense of enlightenment. It seems to me that in order to accomplish this we must abandon beliefs as whatever the wholly other may be, it is necessarily not what we believe it to be otherwise it wouldn’t be wholly other, i.e., entirely different from what we know and feel. In this sense, I feel it is less that we are required to “destroy” fear and belief, but perhaps more to merely accept them as transitory and imperfect: perhaps as veils which hide and distort an enlightened state of being.

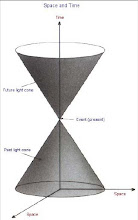

In the end, I agree that it takes a lot of courage to realize that basically we know nothing—or not much of anything, anyway. There seems to be a feedback/forward loop where beliefs about our world come to form what we take as knowledge, and this same knowledge then constitutes grounds for our beliefs about the world: a self-referencing, self-perpetuating network of illusions which allows us to dwell in the castles we’ve built in the air. Indeed, it “takes guts” to jump into the void with hope of hitting some sort of ground.

Monday, November 10, 2008

Saturday, November 1, 2008

(Re)Search

I’ve been thinking about the relation, or possible identity, between paradox, contradiction, and duality. As such, I’ve been doing some research into a few concepts from logic. 1.

I came across this take on the rule that anything follows from a contradiction. While the student’s exposition doesn’t explain it formally like on the wikipedia page, it’s nice to see someone who gets a sense of what follows from this principle: literaly anything is possible. And that’s what has always intrigued me since the first time this rule was shown to me, back in Logic I, some nine years ago. Perhaps others in my class were puzzled and incredulous like the author mentions in her piece, but me, hell, I was smiling because this explains everything.

Well, I bet I didn’t quite think exactly that at the time—I do know that in my head it entirely justified why magick works, and was directly linked to a cornerstone principle of occult thought: nothing is true, everything is possible—it took me a little longer to recognize the importance of this principle.

Another facet of logic I’ve been reacquainting with is proof by reductio ad absurdum. It’s apparent that there is a relationship between the structure of the reductio and the Principle of Explosion mentioned above: they both rely on contradiction, the structure of which can be expressed as A & ~A.

Of course, this brings in my old friend and sparring partner, the law of the excluded middle, which states that for anything, x, x either has the property P or it does not. In predicate logic, this is written Px v ~Px, which in the more basic symbolic logic is P v ~P, and we can simply substitute A for P and get A v ~A.

So we’ve got A & ~A, and A v ~A: like complements of One & Other, like a duality.

But then here’s a bit of self-referencing of sorts because I feel the structure of an understanding of duality goes something like ((A & ~A) & (A v ~A) ) & ((A & ~A) v (A v ~A) ). Or perhaps an even longer sentence, but adding more conjuncts and disjuncts simply seems to expand the point that, somehow, this ties together to create an infinitely rich tapestry.

Anyway, a paradox is basically the same thing as the case when the conjunction of A with its negation is true, so we could say that anything follows from a paradox. On the other hand, a reductio derives a truth so long as it discovers a contradiction in some set of premises: it proves the truth of the negation of some assumption which was used to derive the absurdity. So in both cases, we see how contradiction gives rise to some thing.

I guess where I’m trying to go with this, in part, is the idea that paradox and contradiction have an identical logical structure, and it is from this that everything else is created (derived). If anything follows from paradox, this includes self-consistent systems, i.e., an internally consistent set of sentences—a ‘true’ thing, say—can come from contradiction.

1. For potential readers, the symbols used in this entry are parsed as follows: & is ‘and’, v is ‘or’, and ~ is ‘not’. Hrmm, I ought to make something in the side bar about these things!

I came across this take on the rule that anything follows from a contradiction. While the student’s exposition doesn’t explain it formally like on the wikipedia page, it’s nice to see someone who gets a sense of what follows from this principle: literaly anything is possible. And that’s what has always intrigued me since the first time this rule was shown to me, back in Logic I, some nine years ago. Perhaps others in my class were puzzled and incredulous like the author mentions in her piece, but me, hell, I was smiling because this explains everything.

Well, I bet I didn’t quite think exactly that at the time—I do know that in my head it entirely justified why magick works, and was directly linked to a cornerstone principle of occult thought: nothing is true, everything is possible—it took me a little longer to recognize the importance of this principle.

Another facet of logic I’ve been reacquainting with is proof by reductio ad absurdum. It’s apparent that there is a relationship between the structure of the reductio and the Principle of Explosion mentioned above: they both rely on contradiction, the structure of which can be expressed as A & ~A.

Of course, this brings in my old friend and sparring partner, the law of the excluded middle, which states that for anything, x, x either has the property P or it does not. In predicate logic, this is written Px v ~Px, which in the more basic symbolic logic is P v ~P, and we can simply substitute A for P and get A v ~A.

So we’ve got A & ~A, and A v ~A: like complements of One & Other, like a duality.

But then here’s a bit of self-referencing of sorts because I feel the structure of an understanding of duality goes something like ((A & ~A) & (A v ~A) ) & ((A & ~A) v (A v ~A) ). Or perhaps an even longer sentence, but adding more conjuncts and disjuncts simply seems to expand the point that, somehow, this ties together to create an infinitely rich tapestry.

Anyway, a paradox is basically the same thing as the case when the conjunction of A with its negation is true, so we could say that anything follows from a paradox. On the other hand, a reductio derives a truth so long as it discovers a contradiction in some set of premises: it proves the truth of the negation of some assumption which was used to derive the absurdity. So in both cases, we see how contradiction gives rise to some thing.

I guess where I’m trying to go with this, in part, is the idea that paradox and contradiction have an identical logical structure, and it is from this that everything else is created (derived). If anything follows from paradox, this includes self-consistent systems, i.e., an internally consistent set of sentences—a ‘true’ thing, say—can come from contradiction.

1. For potential readers, the symbols used in this entry are parsed as follows: & is ‘and’, v is ‘or’, and ~ is ‘not’. Hrmm, I ought to make something in the side bar about these things!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)